The wind stayed true and gained in velocity. By midmorning it was blowing twenty knots and the waves were growing bigger. If this affected how Mamede sailed his jangada, I didn’t see it. He hadn’t touched the mainsheet since first wrapping it around the calçador, and our course, though not as easily determined by the elevated sun, still cut a path orthogonal to the wind. The only difference was the angle of our deck — it kept getting steeper. Having no experience with jangadas, I didn’t know how hard they could be pushed — what it would take to flip one over. My ignorance in this case did not bring me bliss.

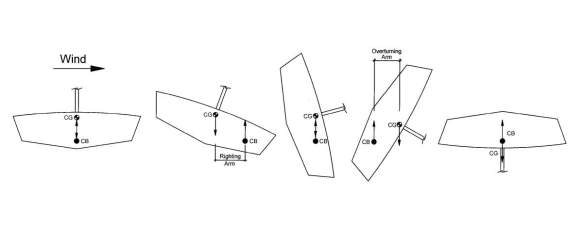

A sailboat with a flat bottom and a hard chine has a lot of initial stability (called stiffness). As the hull heels its center of buoyancy (CB) moves out to counter the turning moment from the sail. Boats with a wider beam will be more stiff because they have a greater righting arm (or lever) to resist the force from the wind. But there are limits to this. The more a boat tips, the more its center of gravity (CG) lines up with the center of buoyancy (reducing the righting arm). If the boat continues to heel, the CG will eventually ride over the CB and beyond. When that happens — Hasta la vista, baby! — buoyancy, once a friend, now becomes the enemy.

As any dinghy sailor knows, the point where a sailboat capsizes isn’t always clear. It can sneak up on you rather quickly. One moment you are sitting high and pretty — the next — face down in the water (just like I was in my first sailing final). All it takes is one good puff to blow you over. Thirty miles offshore, this is not where I wanted to be.

It’s not the end of the world when a jangada capsizes: they are made of wood and have no ballast. Even upside down and filled with water, a jangada will not sink. The hull won’t float very high, due to the density of the wood, but at least you will have something to hold onto. The problem then becomes flipping the boat back. With a flat deck and its rig underwater, an overturned jangada is even more stable than one right side up.

A capsized jangada can be righted. All it takes is patience, skill, hard work, luck, and a boat-load of courage. First you need to lighten the load below the waterline — remove everything from the deck that is weighing it down: unhitch the anchors, remove the mast from the banco, free the fish in the icebox, detach, untie, cut away anything that will keep the hull facing down. “Clear the decks,” you might say, but this deck is now underwater, with rollers rolling and whitecaps breaking. Come up for air, get a mouthful of water — tons of seawater driving you down — down and around, around and down. And if it’s nighttime, you’ll have to do it in the inky dark.

Once the deck has been cleared the air inside the hold will have to be bled. Air gets trapped in the hold because the hatch cover is tied shut while sailing. An overturned jangada filled with air will be impossible to turn over — the same rules of gravity and buoyancy apply. And four men will not be able to overcome those rules with their body weight alone. But they can change the rules — they can make the buoyancy go away. And that is exactly what they do. (They don’t call us Homo Sapiens for nothing.)

Located on the transom of every deepwater jangada is a wooden plug that looks like a large wine cork. Pull the plug and the air bleeds out (it helps to remove the hatch cover first). Eventually the hull sinks low enough to simply roll it over. But there is nothing “simple” about doing this in a running sea. A smart mestre will use the waves to his advantage: swim the jangada around to face the waves, beam on; get his crew on the leeward chine to weigh that side down; wait patiently for the right roller to punch the hull over; repeat four Our Father’s and three Hail Mary’s.

Once the hull is righted the jangadeiros start bailing (after sticking the plug back in). And they bail and bail and bail and bail — trying to stay ahead of the waves that are washing over the deck and filling the hatch. If they are fast enough and lucky enough — each man taking a turn with a cup, pot, or pan — hours later the hull will be up and floating again. They can then step the mast and sail back home. And if the mast is broken the fishermen will jury-rig the longest piece they can find and limp back home.

Every year jangadeiros are lost at sea. Believe it or not, many of them don’t know how to swim. The best they can do is climb onto the overturned hull, hang on and wait. Wait for another jangada to pass by and help (if they are really lucky); wait to be blown ashore (if they are close enough in and the wind is right); wait and hope; hope and wait . . .

I was sitting with Mamede on his porch a couple of days before our trip and asked if he had ever capsized. “Yes,” he replied, “when I was younger.” He then went on to describe the plug-pulling trick. Though the incident had occurred over twenty years before, he recalled it like a recent memory.

“Did you ever flip over again?” I asked.

“No.”

“Did you ever come close?”

“HA! Many times.”

Standing high on the windward side that second morning, watching the green water rush over our submerged lower rail, bits of that conversation kept crossing my mind. At times the deck heeled so steeply I was certain we were going to capsize. Whenever this happened my eyes would dart to Mamede for confirmation that the end was near. But rather than concern, what I saw was a look of quiet concentration. And something else his normally staid countenance could not conceal — pleasure. It was clear from his gleaming eyes and upturned lips that Mamede was having fun, pushing his little boat to the limit.

Seeing his pleasure reassured me, and it also gave me some joy. I didn’t know much about Mamede at the time, having rented a room in his house for only a week; a week he was mostly away fishing. But I was able to get to know his immediate family and this told me a lot about the man. Along with his wife, Dona Graça, there were four kids still living at home, three daughters and a son. Another son was living in Fortaleza to attend high school. (Prainha only had a one-room primary school at the time.) The kids I met were all happy and bright, well mannered and good looking. What more could a parent ask for?

Also living at home were two grandchildren and Mamede’s mother, a tough old bird who scowled whenever I spoke, trying hard to understand my weak Portuguese. Mamede looked just like her.

Mamede supported all of these people with his fishing. It was a huge responsibility, any way you looked at it. And the only job security he had was his own health and the condition of his jangada. There was a local fishing Colônia that provided assistance to fishermen in need. But what the fund could dole out was meager at best — certainly not enough to sustain a large family for very long. As a fisherman you either fished or relied on somebody else who did. The fishing net was the safety net. That and family. Family got you through the hard times.

If all this responsibility weighed heavily on Mamede’s broad shoulders, it didn’t appear to be bothering him that morning. He seemed quite content, putting the jangada up on its rail, knifing us out to deeper water. Seeing him happy made me happy. When the captain is happy, so is the crew.

Next chapter: Ener-gaia

*